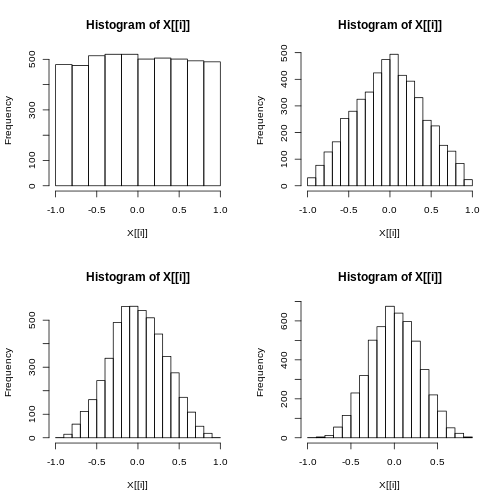

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Joint Probability Distributions ### Sebastian Hoyos-Torres ### 2018-11-01 --- # Joint Probability Distributions - So far, we've covered how to find the probability for a single discrete or continuous variable. - But what if we wanted to find the pmf of two or more random variables? --- # Two Discrete Random Variables - For Discrete random variables, the joint probability mass function is defined by each pair of numbers (x,y) by `$$p(x,y) = P(X=x\text{and} Y = y)$$` `$$\Sigma_{(x,y)\in{E}}p(x,y)$$` - The marginal probability mass functions for X and y are `$$p_x(x) = \Sigma_yp(x,y)$$` .center[**and**] `$$p_y(y) = \Sigma_xp(x,y)$$` - In sum the marginal probability mass functions are just the functions for X considered alone and Y considered alone. --- # Two Continuous Random Variables - If X and Y are two continuous random variables defined on 2-dimensional sample space, space S and if for any event A in S we have `$$\iint{f(x,y)dxdy}$$` - For function f(x,y), then f(x,y) is the joint probability density function for X and Y. - If p(x,y) is the joint probability density function for X and Y, then the marginal probability density functions for X and Y are `$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}f(x,y)dy$$` `$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}f(x,y)dx$$` - As in the discrete case, the marginal probability density functions are just the probability density functions for x considered alone as well as y --- # Joint Distributions - Since the joint probability mass function for continuous and discrete distributions are direct extensions of the single variable discete and continuous distributions and have some of the same properties. - The joint probability mass and denstiy functions are non-negative everywhere. - The sum of p(x,y) over the sample space = 1 - The integral of f(x,y) over the sample space = 1 --- # Example - An insurance company sells both homeowners policies and auto policies. The deductibles on the homeowner's policy is variable Y and X for auto. ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 4 ## x y0 y100 y200 ## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 100 0.2 0.1 0.2 ## 2 250 0.05 0.15 0.3 ``` - The joint would give the probability for each x,y pair so we would have p(100,200) = .2 - The marginal probability mass function of X would be `\(p_x(100) = .2+.1 + .2 = .5\)` --- # Fubini's Theorem If f is continuous on the rectangle R = {(x,y)}|$a\leq{x}\leq{b},c\leq{y}\leq{d}$ then `$$\iint{f(x,y)dA}=\int_{c}^{d}(\int_{a}^{b}f(x,y)dy)dx = \int_{a}^{b}(\int_{c}^{d}f(x,y)dy)dx$$` Assuming the iterated integrals exist and R is the region over which we wish to integrate. To take the double integral, we could take one integral and take the result of that integral to integrate again. --- # Fubini's theorem example: **Example:** Suppose `\(1\leq{x}\leq{2}\)` and `\(0\leq{y}\leq{3}\)`. Show that `\(\frac{2}{21}*x^2*y\)` is a density function. -- `$$\int_{0}^{3}\int_{1}^{2}\frac{2}{21}x^2y dxdy = \int_{0}^{3}\frac{2}{9}ydy = 1$$` --- # Independent Random Variables - Remember: we talked about independence for either 1 discrete or continuous variable thus far. however, what happens when there are 2? - If two discrete random variables are jointly distributed, they are independent when: `$$p(x,y) = p_x(x)*p_y(y)$$` - If two continuous random variables are jointly distributed, they are independent when: `$$p(x,y) = f_x(x)*f_y(y)$$` **If these conditions do not hold, they are dependent** --- # Example of an Independent Random variable (and R code) - Suppose `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)` represent the lifetimes of two components independent of one another. `\(X_1\)` is exponential with parameter `\(\lambda_1\)` and `\(\lambda_2\)`. Then the joint pdf is given by: `$$f(x_1,x_2) = \lambda_1e^{-\lambda_1x_1}\lambda_2e^{-\lambda_2x_2} = \lambda_1\lambda e^{-\lambda_1x_1-\lambda_2x_2}$$` for `\(x_1,x_2\gt{0}\)` Suppose `\(\lambda_1 =1/1000\)` and `\(\lambda_2 = 1/1200\)` then the probability that both lifetimes are at least 1500 hours equals: `$$e^{\frac{1500}{1000}}e^{\frac{1500}{1200}} = .2231*.2865 = .0639$$` In R ```r (1- pexp(1500,1/1000))*(1 - pexp(1500, 1/1200)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.06392786 ``` **However, this only makes sense if they're independent. If not, we use the conditional distributions.** --- # Independent Random Variables- More than Two - If `\(X_1,X_2,...,X_n\)` are all random variables, the joint pmf of the variables is the function: `$$p(x_1,x_2,...,x_n) = P(X_1 = x_1, X_2 = x_2,..., X_n = x_n)$$` - If they are continuous, then `$$P(a_1\leq{x_1}\leq{b_1},...,a_n\leq{x_n}\leq{b_n}) = \int_{a_1}^{b_1}...\int_{a_n}^{b_n}f(x_1,...,x_n)dx_n...dx_1$$` This is similar to the independence of more than two events --- # Conditional Distributions - For continuous random variables X and Y with joint pdf `\(f(x,y)\)` and marginal pdfs f_y(y), the conditional probability density of Y given X=x is: `$$f_{Y|X}(y|x) = \frac{f(x,y)}{f_x(x)} -\infty\leq{y}\leq{\infty}$$` provided that `\(f_x(x)\gt{0}\)` - For discrete random variables X and Y with joint pmf p(x,y) and marginal pmfs `\(p_x(x)\)` and `\(p_y(y)\)` the conditional pmf of Y given X = x is `$$P_{Y|X}(y|x) = \frac{p(x,y)}{p_x(x)}$$` provided that `\(f_x(x)\gt{0}\)` --- # Conditional Distribution - Discrete - Deductible Example An insurance company sells both homeowners policies and auto policies. The deductibles on the homeowner's policy is variable Y, and X for auto represented below <table class="table table-bordered" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> x </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> y0 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> y100 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> y200 </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 100 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.2 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 250 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.05 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.3 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> in our case, suppose x = 100, then `\(p_x(100) = .5\)` and the conditional probability mass function is `\(p_{y|x}(y|100)\)` is: `$$\frac{.2}{.5}:\frac{.1}{.5}:\frac{.2}{.5}$$` --- # A baby donkey in a hammock <img src = "https://media.giphy.com/media/3djolNOedd5pS/giphy.gif"> --- # More on independent random variables! - If X and Y are independent random variables then the conditional distribution of Y given X does not depend upon X and the conditional distribution of X given Y does not depend upon Y. Thus: `$$f_{y|x}(y|t) = f_y(y), f_{x|y}(x|y) = f_x(x)$$` --- # Independent Random variables (Continuous) If X and Y are independent random variables then any probability of the form `\(P(X\leq{x} and Y\leq{b})\)` will equal the product of `\(P(X\leq{a})*P(Y\leq{b})\)`. In the continuous case, it looks as follows: `$$\int_{-\infty}^{b}\int_{-\infty}^{a}f(x,y)dxdy = \int_{-\infty}^{b}\int_{-\infty}^{a}f_x(x)*f_y(y)dxdy = \int_{-\infty}^{b}f_y(y)(\int_{-\infty}^{a}f_x(x)dx)dy = \int_{-\infty}^{b}f_y(y)dy(\int_{-\infty}^{a}f_x(x)dx)$$` Given this, `\(P(Y\leq{b})*P(X\leq{a})\)` --- # Example: Independent Random variables continuous Suppose `\(X_i, i = 1.5\)` is the amount of Nitrous Oxide emissions from a randomly and independently chosen Edsel Engine and each `\(X_i\)` has a weibull distribution with shape parameter a = 2 and scale parameter b = 10. What is the probability that the maximum of the 5 emissions is `\(\leq{12}\)` NOTE: Suppose Y is the maximum. Then `\(Y\leq{12}\)` if and only if each `\(X_i\leq{12}\)`. By independence, we can just figure these out in R ```r pweibull(12,shape = 2,scale = 10) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7630722 ``` ```r pweibull(12,2,10)^5 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.258719 ``` --- # When Independence is Violated - If independence is violated, then we call the variables dependent. If this is the case, we usually want to examine how closely related they are. This leads us to covariance and correlation. --- # Expected Values - The expected value of a function, h(x,y),denoted E[h(x,y)] is defined as for discrete values `$$E[h(x,y)] = \Sigma_x\Sigma_yh(x,y) * p(x,y)$$` for continuous variables `$$E[h(x,y)] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}h(x,y) * f(x,y)dxdy$$` --- # Covariance - The Covariance is defined as: for discrete random variables `$$Cov(x,y) = \Sigma_x\Sigma_y(x-\mu_x)(y - \mu_y)p(x,y)$$` for continuous random variables `$$Cov(x,y) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}(x-\mu_x)(y - \mu_y)f(x,y)dxdy$$` --- # Correlations - The correlation coefficient of X and Y, denoted Corr(X,Y), or `\(\rho_{x,y}\)` or simply `\(\rho\)` is defined as: `$$\rho = \frac{Cov(x,y)}{\sigma_{X}*\sigma{Y}}$$` - For any two rv's X and Y, `\(-1 \leq{\rho}\leq{1}\)` - If a and c are either both positive or negative then, `$$Corr(aX+b,cY+d) = Corr(X,Y)$$` - If X and Y are independent, then `\(\rho = 0\)`. However,$\rho = 0$ does not imply that X and Y are independent. - `\(\rho = -1\)` or `\(\rho = 1\)` if and only if `\(Y = aX+b\)` for some numbers a and b --- # Discrete Example - An insurance company sells both homeowners policies and auto policies. The deductible on the homeowner's policies is variable Y, and X for auto. ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 4 ## x y0 y100 y200 ## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 100 0.2 0.1 0.2 ## 2 250 0.05 0.15 0.3 ``` - The joint pmf would be found by finding the correct x and y pairs in the table. Thus, p(100,100) = 0.1, p(250,0) = 0.05, etc... - The marginal pmf for `\(p_x(100) = \Sigma(px,y) = 0.2 + 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.5\)` --- # The good stuff in R - Although the joint pmf is pretty straightforward, the joint pmf can be easily calculated in R as long as you're careful. Let's store the data we were given into a tibble. ```r testdata <- tibble(x = c(100,250),y0 = c(0.2,0.05),y100 = c(0.1,0.15), y200 = c(0.2,0.3)) ``` This command stores the tibble. You can make this into a dataframe too. ```r sum(testdata[testdata$x == 100,2:4]) #since we are keeping the pmfs in cols 2-4, we need to index them. ``` ``` ## [1] 0.5 ``` ```r testdata %>% filter(x == 100) %>% dplyr::select(starts_with("y")) %>% summarise(joint_pmf = sum(y0,y100,y200)) #this is longer but more explicit. ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 1 x 1 ## joint_pmf ## <dbl> ## 1 0.5 ``` --- # Expected values and variances in R We can also find the expected values and variances through R. Let's create two different vectors as follows: ```r x <- testdata$x px <- c(.5,.5) (ex <- sum(x*px))#expected value of X ``` ``` ## [1] 175 ``` ```r ex2 <- sum(x^2*px) #E(X^2) (vx <- ex2-ex^2) ``` ``` ## [1] 5625 ``` ```r (sd <- sqrt(vx)) ``` ``` ## [1] 75 ``` --- # Can you find the expected value and Variance for Y? <img src = "https://media.giphy.com/media/uzZh2psw4J3ri/giphy.gif"> --- # Solution for expected value and variance of Y - We would just need to find the marginal pmf of Y ```r y <- c(0,100,200) py <- c(.25,.25,.5) #look at the marginal pmf of Y (ey <- sum(y*py)) ``` ``` ## [1] 125 ``` ```r (ey2 <- sum(y^2*py)) ``` ``` ## [1] 22500 ``` ```r (vy <- ey2 - ey^2) ``` ``` ## [1] 6875 ``` ```r (sdy <- sqrt(vy)) ``` ``` ## [1] 82.91562 ``` --- --- # Covariance and Correlation in R - We can also compute the covariance and correlation in R. ```r exy <- sum(100*0*.2,100*100*.1,100*200*.2) exy <- sum(exy, 250*0*.05,250*100*.15,250*200*.3) exy ``` ``` ## [1] 23750 ``` ```r covxy <- exy-ex*ey covxy ``` ``` ## [1] 1875 ``` ```r corr <- covxy/(sd*sdy) corr ``` ``` ## [1] 0.3015113 ``` --- # The Big Question: So What is a statistic? - So far, we have been talking about *probability* and ideal distribution types (whether continuous or discrete). - A statistic is any value that can be calculated from sample data (these values typically inform you about the sample). - Since a statistic is calculated from sample data, which are the values of random variables; a statistic is a random variable. - Prior to collecting the data, there is uncertainty about the value of the statistic. Thus it has a distribution. - Once we collect the data, we evaluate the observed value of the statistic. - To evaluate the distribution of the statistic, we must consider not only the sample we observed but the possibility of other samples that we could have observed. --- # Application Let's say that there are two traffic lights on a commuter's route to and from work. Let `\(X_1\)` be the number of lights at which the commuter must stop on his way to work, and `\(X_2\)` be the number of lights at which he must stop when returning from work. Suppose that these two variables are independent, each with the probability mass function given by: ``` ## [,1] [,2] [,3] ## x 0.0 1.0 2.0 ## px 0.3 0.1 0.6 ``` a) Determine the pmf of `\(T_0 = X_1+X_2\)` b) Calculate the mean of `\(X_1\)` c) Calculate the mean of `\(T_0\)` d) Calculate the variance of `\(X_1\)` e) Calculate the variance of `\(T_0\)` f) How are the various means and variances related? --- # Application continued - Let's note that `\(T_0\)` can take on the values 0,1,2,3,4 (note the mins and maxs of `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)`). From this, assuming independence, we can just use the properties of independence to figure things out. ```r trafficpmf <- tibble( X1_and_X2 = c("0,0","0,1","0,2","1,0","1,1","1,2","2,0","2,1","2,2"), px1_x2 = c(.3*.3,.3*.1,.3*.6,.1*.3,.1*.1,.1*.6,.6*.3,.6*.1,.6*.6), sumx1_x2 = c(0,1,2,1,2,3,2,3,4)) trafficpmf ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 9 x 3 ## X1_and_X2 px1_x2 sumx1_x2 ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 0,0 0.09 0 ## 2 0,1 0.03 1 ## 3 0,2 0.18 2 ## 4 1,0 0.03 1 ## 5 1,1 0.01 2 ## 6 1,2 0.06 3 ## 7 2,0 0.18 2 ## 8 2,1 0.06 3 ## 9 2,2 0.36 4 ``` --- # Application cont. - All we need to do now is add the corresponding probabilities we generated together. ```r t0pmf <- trafficpmf %>% group_by(sumx1_x2) %>% summarise(pt0 = sum(px1_x2)) %>% ungroup() t0pmf ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 5 x 2 ## sumx1_x2 pt0 ## <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 0 0.09 ## 2 1 0.06 ## 3 2 0.37 ## 4 3 0.12 ## 5 4 0.36 ``` --- # Application continued - Let's now calculate the mean and variance of `\(X_1\)`. Just use the formula for the expected value of a discrete random variable. ```r (ex <- sum(traffic[1,]*traffic[2,])) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.3 ``` ```r (ex2 <- sum(traffic[1,]^2*traffic[2,])) ``` ``` ## [1] 2.5 ``` ```r (vx <- ex2-ex^2) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.81 ``` --- # Application continued - The question asked us to do the same for `\(t_0\)` so lets do that quickly ```r (t0ex <- sum(t0pmf$sumx1_x2*t0pmf$pt0)) ``` ``` ## [1] 2.6 ``` ```r (t0ex2 <- sum(t0pmf$sumx1_x2^2*t0pmf$pt0)) ``` ``` ## [1] 8.38 ``` ```r (t0vx <- t0ex2-t0ex^2) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.62 ``` **Do you notice anything about these results?** --- # What we were supposed to notice - In the example, `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)` were independent and `\(T_0 = X_1 + X_2\)` - Also, since `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)` have identical distributions, they also have the same expected values and the same variances. - We also demonstrated the following: `\(E(X_1+X_2) = E(X_1)+E(X_2)\)` and `\(V(X1+X2) = V(X_1) + V(X_2)\)` - The first relationship holds whenever `\(E(X_1)\)` and `\(E(X_2)\)` exist - The second relationship holds when `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)` are independent. --- # Random samples - Evaluating the distribution of a statistic from a sample with an arbitrary joint distribution is often difficult. - To counter this, we typically make the simplifying assumption that our data constitute a random sample `\(X_1,X_2,...X_n\)` from a distribution. This means that: - The `\(X_i\)`'s are independent. - all the `\(X_i\)`'s have the same probability distribution. --- # Simulations (Or what are those r + distribution name functions good for?) - You may have noticed along the course that we have been using a host of functions to generate the pmfs, cdfs and quantiles for a variety of probability distributions. - We left one function untouched however and those were the functions that began with r - R + distribution name functions such as rnorm, rpois,etc. generate a series of random variables from the theoretical distribution which we are interested in. So let's finally try some of the distribution functions out. - These also allow us to examine the distribution or forms of the statistic. --- # Trying out the r family of functions Our results will be different because we aren't setting our seed which would affect the operation of the r family of functions. Let's say we wanted to simulate a distribution with a sample size of 30 from a normal distribution such that X~N(65,3) ```r xsim <- rnorm(n = 30,mean = 65,sd = 3) head(xsim) ``` ``` ## [1] 65.00266 68.57784 61.08447 63.14884 65.98282 62.53087 ``` ```r mean(xsim) #note the mean of xsim seems pretty close to the mean of the distribution it was drawn from ``` ``` ## [1] 65.87247 ``` ```r sd(xsim) #and so is the standard deviation. ``` ``` ## [1] 3.106282 ``` **Try it on your own and see what you get.** --- --- # Simulation of the Normal Distribution - Remember: the statistic in and of itself is a random variable. So how do you think their means and standard deviations will behave if we sample a lot of them? - While we're at it, if we sample a lot of them, how will the distribution of the mean of each sample look like? - Let's bring out the R --- # The R way to simulate Let's say we wanted to calculate the sample mean of 1000 samples of size 30 with each sample being drawn from the normal distribution ```r emptlist <- c() meansimulation <- sapply(1:1000, function(k){ emptlist[k] <- mean(rnorm(30,65,3)) }) #using the apply family of functions in R # or using a for loop (up to you for the purposes of this class) meansimulationloop <- c() for (i in 1:1000) { meansimulationloop[i] <- mean(rnorm(30,65,3)) } head(meansimulation);head(meansimulationloop) ``` ``` ## [1] 64.05004 65.42210 64.56844 65.30873 65.90043 65.01402 ``` ``` ## [1] 64.93807 64.75069 64.89256 64.15106 65.60062 63.64884 ``` **Now that we have the simulation stored, let's do some exploring** --- # Exploration of our simulation - Lets examine the distribution of the means that we just generated. ```r mean(meansimulation) #approximately 65 ``` ``` ## [1] 65.03606 ``` ```r sd(meansimulation) #this changes significantly but we will explain this later. ``` ``` ## [1] 0.5520281 ``` ```r qplot(meansimulation,geom= "histogram") ``` <img src="week6_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-18-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Some notes from our exploration - We saw that the simulated means of the means is almost 65 which is the true mean. - The histogram shows that the distribution of the means looks bell shaped and normal. - The simulated standard deviation **does not** equal to the population standard deviation of 3 but is approximately the population standard deviation divided by the square root of n. - We could continue this experiment with any of the distributions. Would you like to try a simulation? --- --- # Properties of the sample mean and sample sum - Let `\(X_1,X_2,X_3,...,X_n\)` be a random variable from a distribution with mean value `\(\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\sigma\)`. Then - `\(E(X) = \mu_x = \mu\)` - `\(V(X) = \sigma^2/n\)` and `\(\sigma_x = \sigma/\sqrt{n}\)` (this is often known as the standard error of the mean) - Let `\(T_n = X_1 + X_2 + X_3 + ... +X_n\)` be the sample total. Then : - `\(E[T_n] = n\mu\)` - `\(V[T_n] = n\sigma^2\)` and `\(\sigma_T = \sqrt{n\sigma}\)` - If the distribution of the `\(X_i\)`'s is normal, then the distribution of `\(\bar{X}\)` and `\(T_n\)` is also normal. - In other words Averaging moves probability towards the center whereas totaling spreads probability out over a wider range of values. --- # Example In a notched tensile fatigue test on a titanium specimen, the expected number of cycles to first acoustic emission (used to indicate crack initiation) is `\(\mu = 28,000\)` and the standard deviation of the number of cycles is `\(\sigma = 5000\)` Let `\(X_1,...,X_{25}\)` be a random sample of size 5 where `\(X_i\)` is the number of cycles on a different randomly selected specimen. Find the standard error of the mean and the standard deviation of `\(t_0\)`. ```r mu <- 28000 sigmas <- 5000 n <- 25 sigmas/sqrt(n) #standard error of the sampling mean. ``` ``` ## [1] 1000 ``` ```r sqrt(n*sigmas) #standard deviation of T0 ``` ``` ## [1] 353.5534 ``` **Note: if the sample size increases,the mean will remain unchanged but the standard error will decrease. Why?** --- # The Central Limit Theorem - Let `\(X_1,X_2,X_n\)` be a random sample from a distribution with mean `\(\mu\)` and variance `\(\sigma^2\)`. Then for n sufficiently large, `\(\bar{X}\)` has approximately a normal distribution with mean = `\(\mu\)` and variance = `\(\sigma^2/n\)` Formally, the formula for the distribution is: $$\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} ~ N(0,1) $$ - The larger the value of n, the better the approximation. - For distributions that are continuous and reasonably close to being symmetric, the convergence to the normal distribution is good for even small values of n. --- # The example of the uniform distribution: Let's examine some code for simulations. In R, to generate random values from the normal distribution is through the runif. Let's start some simulations! ```r means1 <- means2 <- means3 <- means4 <- c() for (i in 1:5000){ means1[i] <- mean(runif(1,-1,1)) means2[i] <- mean(runif(2,-1,1)) means3[i] <- mean(runif(3,-1,1)) means4[i] <- mean(runif(4,-1,1)) meanslist<- list(means1,means2,means3,means4) } ``` --- # Visuals ```r par(mfrow= c(2,2)) lapply(meanslist,hist) ``` <!-- --> ``` ## [[1]] ## $breaks ## [1] -1.0 -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 ## ## $counts ## [1] 479 476 514 520 520 501 505 501 494 490 ## ## $density ## [1] 0.479 0.476 0.514 0.520 0.520 0.501 0.505 0.501 0.494 0.490 ## ## $mids ## [1] -0.9 -0.7 -0.5 -0.3 -0.1 0.1 0.3 0.5 0.7 0.9 ## ## $xname ## [1] "X[[i]]" ## ## $equidist ## [1] TRUE ## ## attr(,"class") ## [1] "histogram" ## ## [[2]] ## $breaks ## [1] -1.0 -0.9 -0.8 -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 ## [15] 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 ## ## $counts ## [1] 30 77 127 165 253 280 325 352 424 474 494 415 393 331 246 225 152 ## [18] 130 84 23 ## ## $density ## [1] 0.060 0.154 0.254 0.330 0.506 0.560 0.650 0.704 0.848 0.948 0.988 ## [12] 0.830 0.786 0.662 0.492 0.450 0.304 0.260 0.168 0.046 ## ## $mids ## [1] -0.95 -0.85 -0.75 -0.65 -0.55 -0.45 -0.35 -0.25 -0.15 -0.05 0.05 ## [12] 0.15 0.25 0.35 0.45 0.55 0.65 0.75 0.85 0.95 ## ## $xname ## [1] "X[[i]]" ## ## $equidist ## [1] TRUE ## ## attr(,"class") ## [1] "histogram" ## ## [[3]] ## $breaks ## [1] -1.0 -0.9 -0.8 -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 ## [15] 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 ## ## $counts ## [1] 1 15 58 112 162 243 338 490 558 559 541 510 441 346 276 172 109 ## [18] 49 19 1 ## ## $density ## [1] 0.002 0.030 0.116 0.224 0.324 0.486 0.676 0.980 1.116 1.118 1.082 ## [12] 1.020 0.882 0.692 0.552 0.344 0.218 0.098 0.038 0.002 ## ## $mids ## [1] -0.95 -0.85 -0.75 -0.65 -0.55 -0.45 -0.35 -0.25 -0.15 -0.05 0.05 ## [12] 0.15 0.25 0.35 0.45 0.55 0.65 0.75 0.85 0.95 ## ## $xname ## [1] "X[[i]]" ## ## $equidist ## [1] TRUE ## ## attr(,"class") ## [1] "histogram" ## ## [[4]] ## $breaks ## [1] -1.0 -0.9 -0.8 -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 ## [15] 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 ## ## $counts ## [1] 1 4 12 55 115 230 320 501 570 675 640 596 496 350 220 137 51 ## [18] 23 4 ## ## $density ## [1] 0.002 0.008 0.024 0.110 0.230 0.460 0.640 1.002 1.140 1.350 1.280 ## [12] 1.192 0.992 0.700 0.440 0.274 0.102 0.046 0.008 ## ## $mids ## [1] -0.95 -0.85 -0.75 -0.65 -0.55 -0.45 -0.35 -0.25 -0.15 -0.05 0.05 ## [12] 0.15 0.25 0.35 0.45 0.55 0.65 0.75 0.85 ## ## $xname ## [1] "X[[i]]" ## ## $equidist ## [1] TRUE ## ## attr(,"class") ## [1] "histogram" ``` **An Important note! As sample size gets larger, the sampling distribution of the means becomes more bell shaped and more concentrated** --- # Looking at the statistics - How about the statistics of these distributions? ```r data.frame(EX = unlist(lapply(meanslist, mean)),sd = unlist(lapply(meanslist,sd)), trsd = unlist(lapply(1:4,function(x)(sqrt(3)/3)/sqrt(x)))) ``` ``` ## EX sd trsd ## 1 0.0016859584 0.5718055 0.5773503 ## 2 -0.0049474026 0.4087197 0.4082483 ## 3 -0.0005440291 0.3320445 0.3333333 ## 4 0.0054696147 0.2856265 0.2886751 ``` --- # Why the normal distribution is the best distribution - Throughout the course, everyone may have noted my fascination with the normal distribution. Besides the fact that I just like it, it has the following really useful properties. Let `\(X_1,X_2,X_n\)` be a random sample from a normal distribution with a mean `\(\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\sigma\)`. For any `\(n>0, \bar{X}\)` is normally distributed with mean `\(\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)`. Additionally, `\(T_0 = X_1 + X_2 +...+X_n\)` has a normal distribution with mean `\(n\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\sqrt{n\sigma}\)`. If we have a normal distribution and we know the mean and standard deviations, then we can calculate the probabilities (using pnorm or through standardization) and know everything about the distribution. --- # The Normal Distribution continued. - If n is large enough (n > 30) we don't need normality. By the central limit theorem, if n is large enough and `\(X_1,...,X_n\)` is a random sample with mean `\(\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\sigma\)`, then `\(\bar{X}\)` is approximately normally distributed with mean `\(\mu\)` and sd `\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)` - `\(T_0 = X_1+X_2 + ...+ X_n\)` has approximately a normal distribution with mean `\(n\mu\)` and standard deviation `\(\sqrt{n\sigma}\)`. We can calculate the probabilities as if they were normal. --- # Example The time it takes a randomly selected rat to find its way through a maze is a normally distributed random variable with `\(\mu = 1.5\)` mins and `\(\sigma = .37\)`mins. Suppose 6 rats are selected. Let `\(X_1...X_6\)` denote their times in the maze. Assuming the `\(X_i's\)` to be a random sample from the normal distribution, what is the probability that the total time `\(T_0 = X_1+...+X_6\)` for the six is between 8 and 10 mins --- # Example worked out - To find the mean of `\(T_0\)` has a normal distribution with `\(\mu_{T_{0}} = n\mu\)` therefore: ```r 6*1.5 ``` ``` ## [1] 9 ``` - To find the variance use `\(n\sigma^2\)`: ```r 6*0.36^2 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7776 ``` - To find the standard deviation, simply plug into the formula `\(\sqrt{n}*\sigma}\)` ```r sqrt(6)*0.36 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.8818163 ``` ```r sqrt(.7776) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.8818163 ``` - With these values, we are ready to start calculating the probability that the time is between 8 and 10 minutes. --- # Example worked out continued - All we have to do is use pnorm and treat this as a nonstandard normal distribution ```r pnorm(10,9,sqrt(.7776))- pnorm(8,9,sqrt(.7776)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7432151 ``` --- # Linear combinations and their means - Given a collection of random variables `\(X_1,X_2,...,X_n\)` andn numerical constants `\(a_1,a_2,...,a_n\)`, thus the random variable `$$Y = a_1X_1 + a_2X_2 +...+ a_nX_n$$` is a linear combination of `\(X_is\)` whether or not the observations are independent, thus: `$$E[a_1X_1+a_2X_2+,...,+a_nX_n] = a_1E(X_1)+a_2E(X_2)+... + a_nE(X_n)$$` --- # The Variance of linear combinations - If `\(X_1,X_2,...,X_n\)` are independent with variances `\(\sigma^2_1,\sigma^2_2\,...,\sigma^2_n\)`, then: `$$V(a_1X_1+a_2X_2 + ... +a_nX_n) = a^2_1\sigma^2_1+a^2_2\sigma^2_2+...+a^2_n\sigma^2_n$$` --- # The difference between random variables - A common special case of linear combinations is the difference of random variables `\(Y = X_1-X_2\)`. That is, `\(n = 2\)`, `\(a_1 = 1\)` and `\(a_2 = -1\)` - The mean of the difference of Y is `\(\mu_1-\mu_2\)`. In other words, the mean of the difference is the difference of the means. - If `\(X_1\)` and `\(X_2\)` are independent, then the variance of the difference is `$$V(Y) = V(X_1) + V(X_2)$$` This means that the variance of the difference is the sum of the variance. **IMPORTANT: This does not mean standard deviations add!**