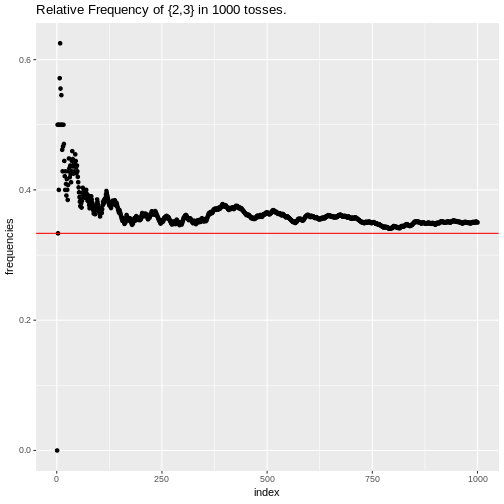

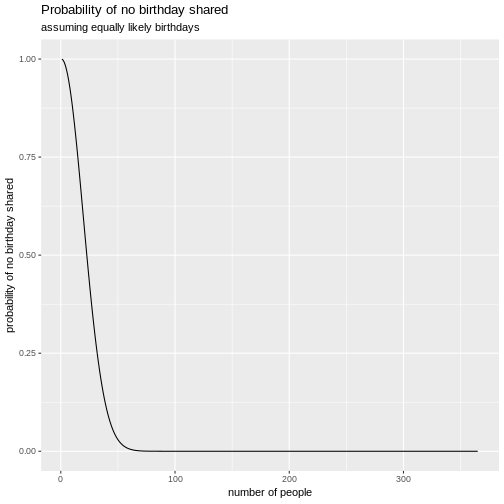

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Introduction to Probability ### Sebastian Hoyos-Torres --- ## Outline: - In this section, we will cover the following: - Sample Spaces and Events - Properties, Axioms and Interpretations of Probability - Definitions of Probability - Equally likely probability spaces and counting techniques - Conditional Probability - Independence --- ## The Uncertain World - Often, we are faced with questions of uncertainty. For example; - How likely is it that you win the powerball? - If you intend to have children until you have at least one child of each sex then how many children will you have on average? - How many traffic lights will be red on your trip to the store? --- ## Key Terms - **Experiment**: any action or process where the outcome is subject to uncertainty. - **Sample Space**: Set of all possible outcomes of an **experiment**. - **Note**: Size of the set is NOT the sample space - **Event**: any subset of a sample space. - **Simple Event**: event consisting of a single outcome. - **Compound Event**: Consists of more than one outcome. - **Probability Function**: gives the probability for each outcome within the sample space. --- #Some useful notation to keep in mind in this section - `\(\Omega\)` : indicates the sample space. Also can be denoted as S or U - `\(\in\)` :Indicates that an element is a member of a set (e.g `\(a \in \Omega\)`) - `\(\emptyset\)`: Indicates the empty set in set theory. In probability, it is known as the empty event. Also known as the **impossible event** - `\(\cup\)`: Indicates a union between elements. For example `\(A \cup B\)` reads as "A or B" - `\(\cap\)` Indicates an intersection between elements. For example `\(A \cap B\)` reads as "A and B" - `\(A^C\)`: Indicates a compement.In this case it would indicate "the elements not in A" - `\(|\)` : Reads as "Given" --- ## Examples - To understand the definitons better, let's see a few examples - Tossing a coin. Within a coin flip, there are 2 possible outcomes. The **sample space ** in this example is {H,T}. In this case a *simple event* will be {H}. - This changes when you toss a coin twice. Instead of {H,T}, now you can have {0,1,2} corresponding to the number of heads appearing. Another is {HH,HT,TH,TH} corresponding to the first, second toss. In this sample space, the event of getting one heads can be represented by {HT,TH} - Let Y mean you scored in the 85th percentile and N mean you did not. The sample space in this case would be an infinite discrete on with {Y,NY,NNY,...} - However, the even you do not take the GRE more than 3 times would look like {Y,NY,NNY} --- ## Examples: Cont - Consider choosing a random strand of hair from the interval `\(S = (0,100)\)` . What would be some possible events? - In this example, which is infinite and continuous, we could say some possible events are `\(A = {{x|0 \le x \le 1}}\)` which is a **compound event** or `\(B = {10.55}\)` which is a simple event. - **Important**: Sample Spaces can be finite and discrete, infinite and discrete, or infinite and continuous. --- ## Approaches to probability - We are familiar with some approaches to probability. Among the most common are the following - Personal Opinion Approach - relative frequency approach `$$P(A) = \frac{N(A)}{n}$$` - The Classical approach `$$P(A) = \frac{N(A)}{N(S)}$$` --- ## Relative Frequency vs. classical approaches to probability - With Relative frequency, we are typically concerned with counts. For example, if we tossed a six sided die 1000 times, how many times would we get `\(E = \{2,3\}\)` ```r library(tidyverse) E <- c(2,3) #set up the event n <- 1000 #sample rolldie <- function(n){ sample(1:6,n, rep = T) } result1 <- rolldie(n) sum(result1 %in% E) #This will give you the number of times E occurred ``` ``` ## [1] 350 ``` ```r table(result1)# see a table of the results. These shouldn't vary too much ``` ``` ## result1 ## 1 2 3 4 5 6 ## 152 179 171 176 151 171 ``` --- ## Visual of the relative frequency approach <!-- --> --- ## Relative vs classical cont. - For the following problem, we could use the classical approach. If you draw a card from a deck of 52 cards what is the probability that a 2,3, or 7 is drawn? ```r n <- 52 result2 <- 3*4 #amount of cards in a standard deck that are a 2,3, or 7 result2/n #or 12/52 to be more exact ``` ``` ## [1] 0.2307692 ``` --- ## Using the language of Set Theory examples - Assume we randomly select a student to see how many shirts they have. Using the notation we just learned, we'd set up the problem as follows: `$$\Omega = \{0,1,2,3,...\}$$` .center[**Or**] `$$S = \{0,1,2,3,...\}$$` .center[**The sample space at this point is infinite and continuous**] .center[ Let's say we had events C which is the randomly selected student owns no more than 5 shirts `$$C = \{1,2,3,4,5\}$$` and D which is that the number of shirts owned is odd so that `$$D = \{1,3,5,7, ...\}$$` ] .center[What would `\(C \cup D\)` equal? `\(C \cap D\)` ? What if `\(C = \{0\}\)` and `\(D = \{1,3,5,7, ...\}\)`] --- ## The R way - Like most things in this course we can do some of this in R to get the intersection and union results ```r C <- c(1:5) D <- seq(from = 1, to = 100, by = 2) union(C,D) # Union ``` ``` ## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 ## [24] 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 ## [47] 89 91 93 95 97 99 ``` ```r intersect(C,D) #Intersection ``` ``` ## [1] 1 3 5 ``` --- ```r #likewise if we do the second step C2 <- 0 D2 <- seq(from = 1, to = 100, by = 2) union(C2,D2) ``` ``` ## [1] 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 ## [24] 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 89 ## [47] 91 93 95 97 99 ``` ```r intersect(C2,D2) #this will return an empty value because it is an empty set ``` ``` ## numeric(0) ``` --- ## The Venn Diagram - We can also depict things pictorially through a Venn Diagram. <img src="https://www.onlinemathlearning.com/image-files/xvenn-diagrams.png.pagespeed.ic.lfu_eFuUlc.png" width="600" height="400"> --- ## Question Slide - Using Venn Diagrams, verify the following - `\((A \cup B)^C = A^C \cap B^C\)` - `\((A \cap B)^C = A^C \cup B^C\)` - Using R or working it out by hand, find `\(A \cup (A\cap B)\)` if `\(A = \{1,2,3,4,5\}\)` and `\(B = \{0,2,4,6,8,...\}\)` - If you toss a coin 3 times, which event demonstrates exactly two tails? `\(A = \{HTT,TTH,THT\}\)` `\(B = \{HTH,HHT,THH\}\)` `\(C = \{THH,TTH\}\)` - Write out in mathematical notation the event that you get two or more heads. --- ## Axioms of probability - Probabilities have properties which are defined by **axioms**. Thus, Probability can be understood as a real-valued set function that assigns to each event A in the sample space a number P(A) (see Penn State https://onlinecourses.science.psu.edu/stat414/node/27/) - Axiom 1: for any event A, `\(P(A) \geq 0\)` - Axiom 2: `\(P(S)\)` or `\(P(\Omega)\)` = 1 - Axiom 3: If `\(A_1,A_2,A_3,...\)` is an infinite collection of disjoint events, then `\(P(A_1,A_2,A_3,...)\)` = `\(\sum_{i=1}^\infty P(A_i)\)` - From these Axioms, we are able to derive other properties regarding probabillity. --- ## Properties of Probability - Prop 1: `\(P(A^C) = 1 - P(A)\)` . This tells us that the probability of the complement of the event is always 1 subtracted by the probability of the event. - Prop 2: For any two events A and B `$$P(A \cup B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A \cap B)$$` - Prop 3: `\(P(\emptyset) = 0\)` - Prop 4: If `\(A_1, A_2, A_3,...,A_n\)` form a partition of the sample space, then `$$\sum_{i = 1}^n P(A_i) = 1$$` - Prop 5: for any events A and B, if `\(A \subseteq B\)` then `$$P(A) \leq P(B)$$` - **A Partition is a mutually exclusive and exhaustive set of events where `\(A_i \cap{A_j} = \emptyset\)` for all i not equal to j** --- ## Properties of Set Operations - Commutativity : `\(A\cup{B} = B\cup{A}\)` - Associativity: `\(A\cup{(B\cup{C})} = (A\cup{B})\cup{C}\)` - Distributive Properties: `\(A\cap{(B\cup{C})} = (A\cap{B})\cup{(A\cap{C})}\)` and `\(A\cup{(B\cap{C})} = (A\cup{B})\cap{(A\cup{C})}\)` --- ## Examples - Let's look at a coin example. If we are tossing a coin, with two simple events {H} and {T}, assignining P(H) = .3 and P(T) = .7 is legal. However, if we assign P(H) = .6 and P(T) = .3, this becomes illegal assignment. Why? - From the textbook (P.57): If we test batteries coming off an assembly line one byone until one having a voltage within prescribed limits is found. The simple events are `\(E_1 = {S}, E_2 = {FS}, E_3 = {FFS}...\)` Suppose the probability of a battery being satisfactory is .99. If we follow this, then how would we go about assigning the probabilities of the simple event? ??? Solution: `\(S = E_1\cup E_2 \cup E_3 \cup ...\)` `\(1 = P(S) = P(E_1) + P(E_2)+ P(E_3)+...\)` remember axioms 1 and 2 `\(.99[1 + 0.01 + (0.01)^2 + (0.01)^3 + ...]\)` This is also conveniently the formula for the sum of a geometric series `\(\frac{a}{1-r}\)` --- ## Counting Techniques - The Product Rule: The Fundamental Principle of counting - Remember that `\(P(A) = \frac{N(A)}{N(S)}\)` - Suppose N operations are to be performed in succession where: -Operation 1 can be performed in **a** different ways. - No matter the outcome of operation 1, operation 2 can be performed in b different ways - No matter the first N-1 outcomes, operation B can be performed in n ways. - Total number of distinct ways n operations can per performed is `$$a \times B \times...\times n$$` --- ## Another example: - Let's look at an example with obstetrician ands physicians. If we have three clinics, and there are 2 physicians and 3 obstetricians within each clinic; how many ways can the family choose their physician and obstetrician if they want to pick from the same clinic to enhance their savings. - The R way ```r phys <- 2 obs <- 3 clinics <- 3 clinics*phys*obs ## this will give you the total number of possble outcomes ``` ``` ## [1] 18 ``` --- ## More examples - Lets say we wanted to see the total number of license plates we could print with 3 letters and four numbers? How many outcomes are possible. ```r # Lets think for a second. # At first, we might be tempted to do 4*3 to get the license plates # However, this is not the right approach because each letter and number has # a certain number of outcomes. So L1 = 26(a-z) total outcomes while N1 = 10 #(0-9). With this in mind, we'd do the following 26*26*26*10*10*10*10 ``` ``` ## [1] 175760000 ``` ```r #or 26^3 *10^4 ``` ``` ## [1] 175760000 ``` - things change if we only want distinct numbers and letters. ```r 26*25*24*10*9*8*7 ``` ``` ## [1] 78624000 ``` ```r #or prod(26:(26-3+1))*prod(10:(10-4+1)) ``` ``` ## [1] 78624000 ``` --- ## The Birthday Paradox - If there are one instructor and 76 students are in a classroom, what is the probability that no student has the same birthday as the instructor? ```r (364/365)^76 ##probability that no student has the same birthday as instructor ``` ``` ## [1] 0.811797 ``` - How about no student sharing a birthday with each other? ```r prod(290:365)/365^76 # the manual way ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0002225625 ``` ```r 1 - pbirthday(76) #using the built in R function ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0002225625 ``` --- ## Further notes on the Birthday Paradox <!-- --> --- ## Perumtations and Combinations - A permutation of n objects taken r at a time, is an ordered subset of r elements taken from a set of n elements. - A combination of n n objects taken r at a time is an unordered subset of r elements taken from a set of n elements - In sum: **Order matters in permutations while order does not matter in combinations** - So `\(P(n,r) = n\times(n-1)\times...\times(n-((r-1)) = n\times(n-1)\times(n-r+1) = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!}\)` - In R this translates to ```r prod(n:(n-r+1)) #or factorial(n)/factorial(n-r) ##avoid using for large numbers as floating point math gets wonky ``` - Then `\(C(n,r)\times r! = P(n,r)\)` **or** `\(C(n,r) = \frac{P(n,r)}{r!} = \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}\)` ```r choose(n,r) ``` --- ## Examples - The draft lottery of 1969 for military service ranked all 366 days (Jan 1, Jan 2, ..., Feb 29, ..., Dec 31) of the year. The men who were eligible for service whose birthday was selected first were the first to be drafted. Those whose birthday was selected second were the second to be drafted. And so on. How many possible ways can the 366 days be ranked? (from: https://onlinecourses.science.psu.edu/stat414/node/29/) - First step is deciding whether order matters or not. - In this case order matters so we'd have `\(366!\)` ways to rank them --- ## More examples: Combinations - In a standard deck of 52 cards using 13 face values and 4 different suits to play 5 card poker. If you are dealt 5 cards, what is the probability of getting a full house? ```r (choose(13,1)*choose(4,3)*choose(12,1)*choose(4,2))/choose(52,5) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.001440576 ``` --- ## Conditional Probability - Often, we have events that influence the probability of other events. In mathematical terms, we often have event B which influences the probability of event A - Thus the conditional probability of A given that B occurred where B is the conditioning event `\(P(A|B)\)` - For any two events A and B with P(B) > 0, P(A|B) is defined by : `$$P(A|B) = \frac{P(A\cap B)}{P(B)}$$` --- --- ## Examples - Roll a die twice, what is the probability that the total we get will be a 3? Given that the first number is 1, what is the probability that the total we get is 3? ```r n<- 6*6 #number of total outcomes 2/n ``` ``` ## [1] 0.05555556 ``` ```r #if given first number is 1 1/n/(1/6) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1666667 ``` --- ## More on conditional probability - The multiplication rule: The probability that two events A and B both occur is given by the multiplication rule `$$P(A \cap B) = P(A|B)\times{P(B)}$$` `$$P(A \cap B) = P(B|A) \times P(A)$$` - Complement Rule: `\(P(A^c|B) = 1 - P(A|B)\)`. **Note: this is not the same as P(A|B^c).The complement rule only corresponds with the first argument** --- ## Example of the multiplication rule - A box contains 6 white balls and 4 red balls. If we randomly (and without replacement) draw two balls from the box, what is the probability that the second selected ball is red? `$$P(R_2) = P[(W_1 \cap R_2)\cup(R_1\cap R_2)]$$` `$$P(W_1 \cap R_2) + P(R_1\cap R_2)$$` `$$P(W_1)\times P(R_2|W_1) + P(R_1)\times P(R_2|R_1)$$` `$$P(R_2) = (6/10) \times (4/9) + (4/10) \times (3/9)$$` ```r (6/10)*(4/9)+ (4/10) * (3/9) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.4 ``` --- ## Multiplication rule extension - We can extend the multiplication rule to three of more events .center[thus:] `$$P(A\cap{B}\cap{C}) = P(C|A\cap{B})\times{P(A\cap{B})}$$` `$$P(C|A\cap{B})\times{P(B|A)} \times{P(A)}$$` --- ## Extension example - Three cards are chosen at random and without replacement from a standard deck of 52 cards. What is the probability of drawing a king, queen, and jack, in that order. `$$P(K_1\cap{Q_2}\cap{J_3}) = P(K_1)\times{P(Q_2|K_1)}\times{P(J_3|(K_1}\cap{Q_2))}$$` `$$\frac{4}{52}\times{\frac{4}{51}}\times{\frac{4}{50}}$$` ```r (4/52)*(4/51)*(4/50) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0004826546 ``` --- ## Law of total probability - Suppose `\(A_1,A_2,...,A_n\)` form a partition of sample space S, then for any event B, it is true that $$P(B) = P(A_1\cap{B})+ P(A_2\cap{B})+...+P(A_n\cap{B}) = $$ `$$P(A_1)\times P(B|A_1)+ P(A_2)\times P(B|A_2) + P(A_n)\times P(B|A_n)$$` - This leads us to a deeper understanding of Bayes Theorem --- ## Bayes theorem - Let n events `\(A_1,A_2,A_3,...,A_n\)` be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Then for any event `\(B\)`, `$$\Sigma_{i = 1}^{n}P(B|A_i)\times P(A_i)$$` - Let n events `\(A_1,A_2,A_3,...,A_n\)` be mutually exclusive and exhaustive with prior probabilities `\(P(A_i)(i = 1,...,n)\)`. Then for any event B for which P(B)>0, the posterior probability of `\(A_j\)` given that event B has occurred is `$$\frac{P(A_j\cap B)}{P(B)} = \frac{P(B|A_j)P(A_j)}{\Sigma_{i = 1}^n P(B|A_i)P(A_i)}$$` --- ## Example of Bayes Theorem at work - Suppose 1 in 1000 adults is afflicted with a rare disease. The test is such that when an individual actually has the disease, a positive result will occur 99% of the time, whereas an individual without the disease will show a positive test result only 2% of the time. If a randomly selected individual is tested and the result is positive, what is the probability that the individual has the disease? ```r PA_1 <- .001 #population that has the disease PA_2 <- .999 #population that does not have the disease ##B indicates a positive test result PBA_2 <- .02 #Positive result given does not have disease PBA_1 <- .99 #positive result given individual has disease ## Bayes approach (PA_1*PBA_1)/((PA_1*PBA_1)+(PA_2*PBA_2)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0472103 ``` --- ## Another Example - A factory has 3 machines. Machine 1 produces 50 percent of output, machine 2 produces 30 percent, machine 3 produces 20 percent. The defective output from each machine is 8, 4, 2 percent respectively. Suppose we randomly select a piece of output. - What is the probability that it is defective? - If it is defective, what is the probability it is from machine 1? ```r A1 <- .5 A2 <- .3 A3 <- .2 PDA1 <- .08 PDA2 <- .04 PDA3 <- .02 PD <- sum((PDA1*A1),(PDA2*A2),(PDA3*A3)) PD ``` ``` ## [1] 0.056 ``` ```r (A1 * PDA1)/PD ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7142857 ``` --- ## Independent events - Two events are independent if `$$P(A\cap{B}) = P(A)*P(B)$$` .center[OR] `$$P(A|B) = P(A),P(B|A) = P(B)$$` - **Note, events are independent if the occurrence of one does not affect the probability of the occurrence of the other** - Events `\(A_1,A_2,A_3,...,A_n\)` are mutually independent if for every `\(k \geq 2\)` and every set of indices `\(i_1,i_2,...,i_k\)` `$$P(A_{i_{1}} \cap{A_{i_{2}}}...\cap{A_{i_{k}}}) = P(A_{i_{1}})P(A_{i_{2}})...P(A_{i_{k}})$$` --- ## Some theorems - If A and B are independent events, then A and `\(B^C\)` are independent - If A and B are independent event, the `\(A^c\)` and `\(B\)` are also independent - If A and B are independent event, the `\(A^c\)` and `\(B^C\)` are also independent --- ## Example: - A nationwide poll determines that 75% of the American population loves eating pizza. If two people are randomly selected from the population, what is the probability that the first person loves eating pizza, while the second one does not? ```r lpizza <- .75 npizza <- 1-lpizza #Probability that first loves pizza while second does not is lpizza*(npizza) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1875 ```